Acknowledgments

I would like to express my great appreciation to Mary Bennett, the Special Collections Coordinator of the State Historical Society of Iowa, for her valuable insights, analysis, and use of photo scanner and access to archival materials. She has been an incredible asset and guide for this essay, and it should be known that her dedication and time to this project is most appreciated.

Also from the State Historical Society of Iowa, I would like to thank Hang Nguyen, who assisted in my research through the retrieval of archival materials. She was an incredible help to my paper, and her contributions are very much appreciated.

I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Diana Underwood, a descendant of Robert Moehn and Hilda Rinker, and my mother, for her diligent caretaking and preservation of the family photograph collection as well as marriage certificates and family trees. She kept records of the family and helped provide critical context for points made in this essay. Diana also was a source of inspiration and guidance.

German immigrant roots run deep in Iowa. Their influences are still felt in businesses, buildings, families, and the ideologies surrounding the Midwest, hidden in some places andgrated to Iowa to start their own stories, bringing their trade with them. Coopers1, brewers, grocers, and carpenters all founded businesses in Eastern Iowa and began the development of the area. The immigration patterns seen through decades of political, economic, and societal troubles in Germany presented German immigrants an opportunity to “colonize” the Midwest. In the 19th century during intense periods of immigration, many German-Americans used the word “colonie” to describe the groups of Germans who were settling in more underdeveloped places in the Midwest.2 One such family that will be analyzed as an example through this narrative is the Moehn family from Bavaria.3 They provide an in-depth look into the world of German immigrants through numerous photographs and postcards, that illustrate just how exactly they experienced Iowa and a political episode of anti-German sentiments. The question that must be faced when looking at German immigrant history is the following: Why did society temporarily shift towards an ethnocentric viewpoint that excluded people of German heritage? And how did those affected by this reversal of political ideologies navigate this uncertain time in American history? German immigrants managed to retain some of their culture, heritage, and identity through their photography and took an active role in the creation of their new developing ethnicity during the changing political sphere that enveloped them during the 1910s and 1920s. This paper will present numerous unarchived and rare photographs as well as primary accounts to show just how German immigrants accomplished this feat.

Photographs have been invaluable to Germans in Iowa. They carried their family albums and pictures with them as they emigrated from their homes in Germany in search of a better and more profitable life. In the 1850s “nearly one million Germans immigrated to America in this decade, one of the peak periods of German immigration; in 1854 alone, 215,000 Germans arrived in this country.”4 The 19th century alone saw this influx of German immigrants as many more continued to leave Germany following political and economic unrest. They continued to leave for America, and in the 1880s “the decade of heaviest German immigration, nearly 1.5 million Germans left their country to settle in the United States; about 250,000, the greatest number ever, arrived in 1882.”5 Hundreds of German publications, newspapers, and businesses began to fully establish themselves in the United States, and in the Midwest in particular. By the 1890s, “An estimated 2.8 million German-born immigrants lived in the United States. A majority of the German-born living in the United States were located in the ‘German triangle,’ whose three points were Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and St. Louis.”6 The German presence in the Midwest and the wider United States was very established by the turn of the 20th century. This is a brief overview of German immigrant history and will be developed throughout this paper. The focus of this paper is in the Midwest and specifically Iowa; however, Germans were widespread throughout the United States, and the wider context of the argued points are applicable. These Germans brought more than just themselves; they brought their trades, ideologies, familial values, religion, and, of course, their photographs.

Photographs served as a connection to and a reminder of their homeland. As an example, the Pfeiffer family, who were also from Bavaria, like the Moehn family, brought their family pictures, two of which were acquired for this essay. The first item is a portrait of Peter Pfeiffer taken in Germany c. 1850s (See Figure 1, additional context is provided to the majority of the figures included in the appendix). Due to the taller angle used to capture a longer image of the torso, when the photograph was approximately taken, and the type of photograph it is, this portrait was European.7 This image is an example of a carte-de-visite8, which were popular around the time of the family’s immigration to the United States in the late 1850s and 1860s. The taller portrait is uncharacteristic of American portraits and is a direct link back to the styles of photographers from Germany. As another link back to their German roots, a tintype9 was also included in their family albums. The tintype depicts Margaret Pfeiffer and was taken back in Bavaria (Figure 2). It has a rare quality to it, as there is added coloring on the cheeks of the subject. The image shares the same characteristics of the previous image, that is, a taller portrait that shows more of the lower torso of the subject. Additionally, tintypes were rather cheap to make, which makes sense as these German families came from small Bavarian villages. The Moehn’s, in particular, were pinpointed to either Dellfeld or Stambach10, which were located in Rhenish Bavaria (now more commonly known as Palatinate), a region of Germany. These photographs from their homes in Germany act as a memento for the family and are a link to their heritage, allowing immigrants to remember those who did not make the journey to the United States. However, most German immigrants did not hold what is referred to as “diasporic imagination,” which is a sense of belonging and obligation to an immigrant’s homeland, garnering a sense of duty towards nationalistic viewpoints. This diasporic imagination did not prevent Germans from fully colonizing their new homes in America, they felt no need to return to the homeland, but rather, were more invested in their success and opportunities in the United States as Germans.11

But what exactly does it mean to be German? This is a question that has plagued historians and even Germans themselves, relating back to the German Question; that is, what to do with Germany and how should it be structured? How did Germans retain or build upon their culture and sense of ethnic identity? The overlooming problem for Germans during this time was anti-German sentiment brewing in the United States up to and after World War I. Through temperance laws and Iowa Prohibition, the Babel Proclamation, and anti-German ideologies becoming prevalent, the ability of the German ethnicity to survive and grow was challenged. The idea of German “ethnicity” is a constructed concept. Many historians and sociologists have been reevaluating what ethnicity truly means. Germany itself is not an easily identifiable people or area. Language groups, state lines, the looming Holy Roman Empire, all contributed to a muddled mess of confusion. However, I will attempt to provide context and work to define what German ethnicity is for these immigrants. Kathleen Conzen writes about this topic, stating that the “dominant interpretation both in American historiography and nationalist ideology had been one of rapid and easy assimilation. Various theories which predicted this outcome, i.e., Anglo-conformity and the Melting Pot, shaped the underlying assumptions of several generations and social scientists.”12 Recently, historians have begun to question these theories, and rather look towards a viewpoint that is more malleable and adaptive.

The perspective of mixed-American ethnicity with old-world traditions seems to hold in the case of German Americans of the late 19th century and early 20th century. Part of the German immigrant experience was learning to adapt to the new culture and society present in America. I have presented photographic evidence of this occurring and will develop this idea of maintaining German “identity” while still evolving into a German American. It is a complicated topic, and historians still debate the concept of ethnicity and the role it had for American immigrants of all backgrounds. The writings of Clifford Geertz and Harold Issacs, who are anthropologists, come to the idea that ethnicity is “‘the basic group identity’ of human beings.”13 Conzen discusses this idea by saying in “this view, persons have an essential need for ‘belonging’ which is satisfied by groups based on shared ancestry and culture.”14 Immigrants can achieve this through their familial ties, communal activities, trades, and religion. Numerous photographs included in this paper exhibit this tendency. Photographs of weddings, social outings, the Moehn Brewery, and beer gardens all show this communion of ancestry and culture being displayed. The formation of group identity is paramount to ethnicity. Kathleen Conzen and the other authors of “The Invention of Ethnicity” differ in their perspective of ethnicity than those of other academics, like Werner Sollors. Conzen states that with ”Werner Sollors, we do not view ethnicity as primordial (ancient, unchanging, inherent in a group’s blood, soul, or misty past), but we differ from him in our understanding of ethnicity as a cultural construction accomplished over historical time. In our view, ethnicity is not a ‘collective fiction’, but rather a process of construction or invention which incorporates, adapts, and amplifies preexisting communal solidarities, cultural attributes, and historical memories. That is, it is grounded in real life context and social experience.”15

Although society in Iowa continually oppressed and challenged German immigrants and citizens of German heritage, they maintained traces of their German “identity” and “ethnicity”. Through photographs, Germans captured what was important to them, that is, their families, their businesses, and their faith. They were patrons of German-ran photography studios and contributed to a society that slowly abandoned and degraded them. Henry Moehn was heralded as a figure of progressive movement and an influential founder of the city of Burlington, but within a few decades, his son would have his business shut down due to Prohibition, and be forced to live through the Babel Proclamation, where thousands of families had to abandon the language of their homelands in favor for a chauvinistic and ethnocentric United States that demanded a strong, cohesive community, but failed to provide that for those it oppressed. The photography of these German immigrants is a testimony to a positive, adaptable, familial heritage that shows the strength and legacy of German Americans in Iowa. Despite an episode of political disparities, German immigrants’ stories and photography help display how Germans were able to navigate the turbulent times of the early 20th century while adapting to a new shared ethnicity of being German as well as Americans.

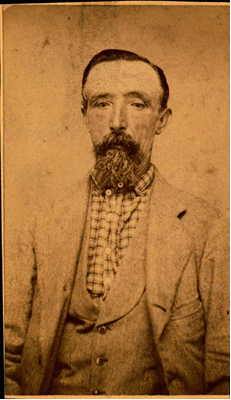

Figure 1

Unknown Photographer, Untitled, Portrait of Peter Pfeiffer, c. 1850

This image was analyzed by Mary Bennet of the Iowa Historical State Society, who provided the context that it was taken in Europe. The Pfeiffers were from Germany, and were also from Bavaria, like the Moehns. The taller image is uncharacteristic of American portrait photography. His shirt is also unlike American fashion at the time, and his pose is very simple, with neither background set nor props. The family came from small towns, so the disclusion of a higher quality studio setting is not surprising. The back of the photograph bears a mark of where a stamp used to be, perhaps contributing to the idea that this photograph was sent to the United States from Germany where it was taken.

Figure 2

Unknown Photographer, Untitled, Portrait of Margaret Pfeiffer, c. 1875

This photograph is a tintype and was approximately taken in the latter half of the 19th century. It resembles the same kind of style of Figure 1, a taller portrait with a simple background. Tintypes were extremely cheap to make, once again adding to the narrative of the poverty Germans faced while living in their homelands during this time. It is a simple portrait, save for the coloring that has been added to the subject's face, namely her cheeks. Her clothes are not too extravagant and provide a rather plain image. The Rinker’s were farmers, and this subject fits that occupation. The tintype was taken in Germany and then found its way to the United States.

Figure 3

Unknown Photographer, Untitled, c. 1910. Photograph of the Moehn Brewing Company and its newly acquired delivery truck with Martin Moehn, owner, on the right and employees on the left.

Martin Moehn is dressed well and strikes a confident, relaxed pose as he seemingly invites the viewer to gaze upon his success, in the form of a new truck. The men on the left are presumably workers, with the two men who are standing in front of the rest most likely being Barney Neiman and John T. Bickman, the Vice President, and the Secretary/Treasurer respectively of the Moehn Brewing Company. This was taken on 923 Osborn St, Burlington Iowa, the location of the brewery, where the company’s sign can still be seen on the side of the building, in c. 1910 at the height of the Brewery’s success. The Moehn crest and logo of the brewery are seen emblazoned on the side of the car, directly below the driver’s seat. This photograph might be the most significant of the collection.

Figure 4

Kauffman’s Studio, Untitled. Group Photograph of a Rainbow Wedding, 1919.

The wedding is between Bertha Moehn, daughter of Martin Moehn and Robert Lee. The coloring of the photograph makes it very unique. The color was hand added in post-production and shows how much these familial photographs meant to these German families. The concept of a Rainbow Wedding is non-American and is a testament to traditions this family had in the past. Mary Bennet of the previously mentioned Iowa Historical State Society stated that the photo was extremely rare, and the coloring is of very high quality. The non-American style wedding provides an example of German families foregoing the Babel Proclamation and the expected homogenized ethnic change into “Americans”, especially since it occurred in 1919 when Babel was still impacting Germans in Iowa.

Notes

1 “Cooper” is a profession of barrel or cask making and repair.

2 Conzen, Kathleen Niels. “Phantom Landscapes of Colonization.” The German-American Encounter Conflict and Cooperation Between Two Cultures, 1800-2000 (2001): p 12

3 A German state that was integrated into the wider Germany following World War I. Furthermore, I will refer to the Moehns as Bavarians through this paper, although I have conflicting records of their origins. I have stated in this paper that they are from villages that would be within the state lines of Bavaria, but other primary sources refer to them as being from Prussia. Their Catholicism makes their Bavarian origins more likely.

4 “The Germans in America.” Chronology: The Germans in America (European Reading Room, The Library of Congress.)

5 “The Germans in America.” Chronology: The Germans in America (European Reading Room, Library of Congress)

6 “The Germans in America.” Chronology: The Germans in America (European Reading Room, Library of Congress)

7 Mary Bennett of the Iowa State Historical Society provided critical context and analysis of the photographs that led to this conclusion. Bennett has helped with the identification of the majority of photographs present in this paper.

8 “Just two and a half by four inchces in size, cartes de viste were the first form of commercial portrait photographs made as multiple paper prints. Cartes were invented in Paris in 1854 (...) ‘Cartes de visite’ translates as ‘visiting card’”. Volpe, Andrea. Cartes de Visite Portrait Photographs and the Culture of Class Formation. Page 158. 1 January 2005.

9 “Tintype, also called ferrotype, positive photograph produced by applying a collodion-nitrocellulose solution to a thin, black-enameled metal plate immediately before exposure. The tintype, introduced in the mid-19th century, was essentially a variation on the ambrotype, which was a unique image made on glass, instead of metal.” The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Tintype, (Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 1 Dec. 2017).

10 These two villages are about 2.5 miles apart. A family chronicle written by the descendant of the Moehn family mentions these two villages, which she estimates as being 5 miles apart, as the ancestral homes of the Moehn family. This chronicle outlines the location and birth dates of all family members identified in this paper unless otherwise specified. See appx. 3. & 4. For photo scans of the chronicle.

11 Conzen, Kathleen Niels. “Phantom Landscapes of Colonization.” The German-American Encounter Conflict and Cooperation Between Two Cultures, 1800-2000 (2001): p 11

12 Conzen, Kathleen Neils, David A. Gerber, Ewa Morawska, George E. Pozzetta, and Rudolph J. Vecoli. "The Invention of Ethnicity: A Perspective from the U.S.A." Journal of American Ethnic History 12, no. 1 (1992) p. 3

13 Conzen, Kathleen, p. 4

14 Conzen, Kathleen, p. 4

15 Conzen, Kathleen, p. 4-5

Works Cited

Andreas, A.T. An Illustrated Atlas of Des Moines County, Iowa. On file at the State Historical Society of Iowa. Lakeside Building, Chicago, Ill. 1873.

Barthel, Diane L. Amana: From Piestist Sect to American Community. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln and London, 1984. Print.

Bennett, Mary. Personal Communication. Fall Semester 2019.

Burlington Des Moines County Biographical Review, Des Moines, Iowa. January 1, 1905. Pages 374-376. Print.

Burlington Hawk Eye Newspaper, Closing Scenes of Liquor Business in Burlington, The Three Breweries. Burlington, Iowa. January 1, 1916, Page 7.

Conzen, Kathleen Neils, David A. Gerber, Ewa Morawska, George E. Pozzetta, and Rudolph J. Vecoli. "The Invention of Ethnicity: A Perspective from the U.S.A." Journal of American Ethnic History 12, no. 1 (1992): 3-41. www.jstor.org/stable/27501011.

Conzen, Kathleen Niels. “Phantom Landscapes of Colonization.” The German-American Encounter Conflict and Cooperation Between Two Cultures, 1800-2000 (2001): 7–21.

Cora Eversmeyer papers, Iowa Women's Archives, The University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City. http://aspace.lib.uiowa.edu/repositories/4/resources/1890

Derr, Nancy. "The Babel Proclamation." Iowa Heritage Illustrated 85 (2004), 128-145. Available at: https://ir.uiowa.edu/ihi/vol85/iss2/7

Burgess, JoAnn. Directory of Iowa Photographers, Pre-1900. Manuscript on file at the State Historical Society of Iowa. 1991.

Ted Rehder Papers, The University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa. http://aspace.lib.uiowa.edu/repositories/3/resources/1590

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Tintype, (Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 1 Dec. 2017).

“The Germans in America.” Chronology : The Germans in America (European Reading Room, Library of Congress). The Library of Congress, April 23, 2014. https://www.loc.gov/rr/european/imde/germchro.html.

Welskopp, Thomas. “‘Prohibition in the United States: The German-American Experience, 1919-1933.’” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute. No. 53. Fall 2013 (2013): 31–53. Print.

Volpe, Andrea. The Middling Sorts; Explorations in the history of the American Middle Class. Cartes de Visite Portrait Photographs and the Culture of Class Formation. Page 158. 1 January 2005.